We’ve all been hearing it on Barley St: poor/low yields, high protein, material shortages… In the current environment, yield is even more important than a typical year. So let’s talk about yield.

To understand all this talk about low barley yields this year, one must first understand what it takes for a good yield. As a starting point, a nice growing season and optimal yields are much more pleasant to talk about. 😊

Full disclosure, my point of reference will be the Bighorn Basin in Wyoming and southern Montana because that’s the area where Briess growers raise barley and it’s located only a half-day drive from my home office.

Components that contribute to yield:

- Favorable fall weather allows farmers to complete fieldwork to be ready for spring planting. That was the case this Fall in the Bighorn Basin, so we should have a good start in 2022.

- It’s important to have enough ground moisture at the time of seeding, followed by rain or snow with enough moisture to bring the crop up. I’ve heard it said that if mother nature brings up the crop, it can mean a 10-20% increase in yield. In general, the earlier seeded barley produces higher yields. Our desire is a cool wet spring to get the crop to stool and make optimal yields. Spring showers really do help keep the crop growing. Sounds pleasant, doesn’t it? That’s because it is. As with life, when things aren’t pleasant, they are stressful. For barley and the growers, plant stress is an enemy. More on stress later…

- Conversely, if you must irrigate the crop up, it can decrease yield by 10%.

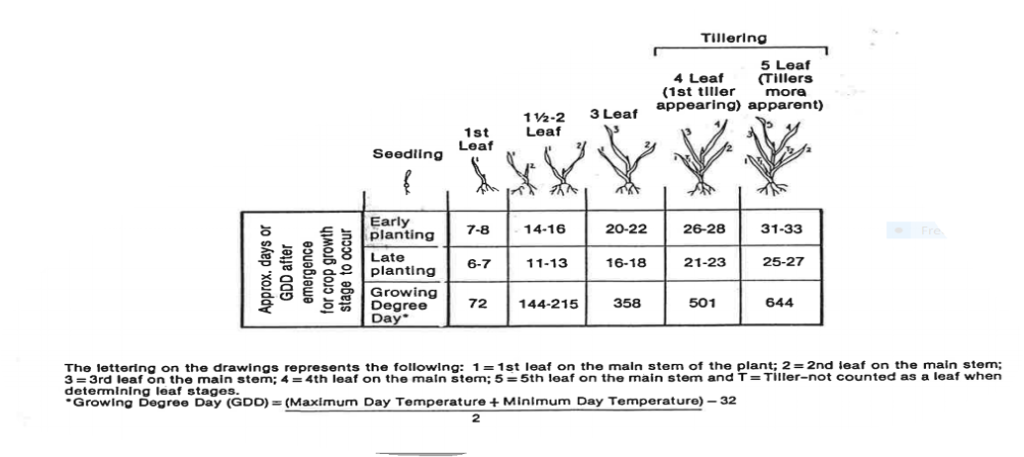

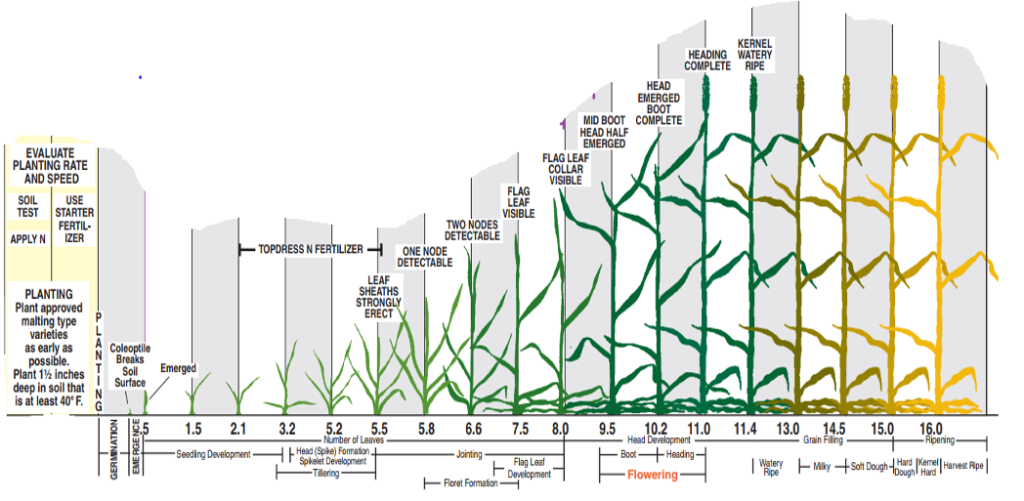

- Weed control and timely spraying contribute to optimal yields. With persistent hot and dry conditions, it is difficult to get herbicides on the crop at the right time while maintaining the proper moisture level.

One barley seed does what? Well, the Reader’s Digest version is that it grows, throws a main shoot, forms a head, and (with proper moisture, warm days, cool nights) the head fills to about 22 kernels. Finally, a hot, dry July finishes things off. Wow, a ratio of 1:22 you say, that’s pretty good. Actually that’s not even close. Under pleasant and low stress conditions, one seed with proper stooling can throw 4-9 tillers, and each tiller develops and forms a head. In optimal growing conditions the heads fill to the same number of kernels as the main shoot. When planting 2.3 bu of IP seed per acre the typical yield is around 110 bu per acre, depending on variety. Low stress growing conditions also allow the heads to fill nicely to meet the plump spec. That’s the multiplier effect to obtain a great yield.

Irrigation is a powerful tool to keep plant stress down and deliver consistently good to excellent yields. Most of our fields in the Bighorn Basin are floodwater irrigated, and I believe that’s what made it possible for Briess to keep 2021 acceptance levels about the same as normal, along with good proteins and good plumps. Barley performs best when flowering and grain filling takes place when temperatures are moderate and soil moisture is adequate. Controlled watering, warm days, cool nights, and low stress equals a better barley life for all. So, the irrigation water greatly helps lower stress but as with the 2021 growing season, there was nothing a farmer could do about the hot nights.

Now a word about the relationship between plant stress and yield… This year many growing regions experienced extremely hot and dry weather, with drought conditions where irrigation was not available. In that environment, the barley plant pulls back and just tries to survive instead of thrive. Head filling can be problematic, with impact ranging from fewer kernels to thins. Depending on the situation, fewer tillers are thrown.

When growing season is challenging and yields decline significantly, there is usually an AND with a disappointing list of specs that follow. High proteins due to stress and thins contribute to low test weights. Once the barley goes through assortment, some thins are not selected resulting in another loss-of-yield point. There are many other challenges for barley farmers. Some planted acres in North America were abandoned and not harvested, thus lowering yields against what was planted.

There are many other challenges for barley growers. Yield can also be negatively impacted by too much water or moisture at the wrong time (fusarium), staining, and pre-sprout at harvest. The latter are often reasons for lower acceptability rates which reduce yield numbers.

If you think brewing is hard, try farming!

Cheers,

Dan