Thanks to the convergence of craft beer and modern drying equipment, American brewers now have more styles of malt at their disposal than any time in history. This installment on malting and Briess Malthouses offers a glimpse at drying operations in the Chilton Malthouse. If you missed the first posts in this series, check them out:

- The Briess Malthouses…then and now

- Part II: Seventy-five steps to steeping

- Part III: The wonderful world of germination

Drying is the third and final step in the malting process, after steeping and germination. Drying is a critical step that stops germination. If germination continued, the kernel would continue to grow and all of the starch reserves needed by the brewer would be used by the growing plant.

Base malts are kiln dried, typically for 2-4 hours with a finish heat of 180-190° F. This develops flavors ranging from very light malty to subtle malty while retaining enzymes necessary for brewing. Specialty malts are dried in a kiln at higher temperatures for longer periods of time, roasted, or both. This develops the unique flavor, color and other characteristics of each specialty malt.

On your mark, get set, stop!

On its way to drying, barley is first steeped for two days, then spends the next four days in the germination compartment where the growing kernels undergo modification—the breakdown of complex proteins and carbohydrates which opens up the starch reserves needed for brewing. After the fourth day the barley is now called “green malt” and ready to be transferred to a kiln or roaster to stop germination. This image illustrates how fast the kernels grow.

Kilned Malt

The majority of malt—base and specialty—is kiln dried. Our ancient ancestors relied upon the sun’s rays to do the job. From wood to coal to natural gas, advances in fuel source and technology have greatly improved the amount of control maltsters have in the kiln. As a result, an exciting variety of kilned malts from Pilsner to Munich-styles are now available for American craft and home brewers alike. The growing number of malting barley varieties available and in development make the malt options even greater!

In addition to being used as base and high temp kilned malts like Munich-styles, kilned malts are often roasted at high temperatures to become dark, rich flavored specialty malts ranging from biscuit to chocolate to black malt.

Roasted Malt

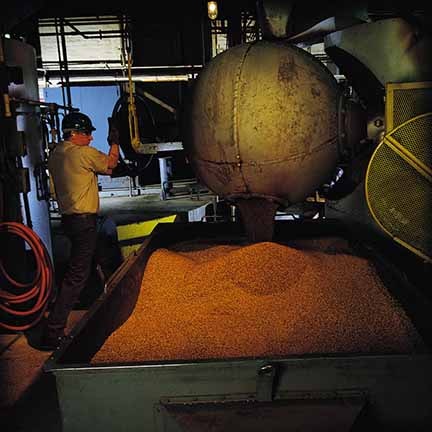

Did you know that Briess started roasting caramel (crystal) malt in the 1950s when it had several German-produced “K-ball” roasters installed in the Chilton Malthouse? More efficient drum roasters were installed in the 1970s, and in the 1990s a second roasting operation was installed at the Waterloo Malthouse.

Briess drum roasters are custom designed and engineered specifically for roasting malt and barley. This custom engineering allows for the application of significantly higher temperatures to green malt, which is a must for the caramelization of sugars, uniform temperature application to all kernels, and precise control of airflow and moisture.

While some maltsters kiln produce caramel malts, Briess roasts its caramel malts. That’s because full, caramel flavors and aromas are not achievable with kilning. Not sure what the difference between caramel and crystal malts are? Check out Bob Hansen’s blog, Is it Crystal or Caramel Malt?

Drum roasters also produce more uniform and consistent results within each batch and from lot to lot of not only caramel, but other roasted malts like Carabrown®, Chocolate, Dark Chocolate and our darkest malt, Midnight Wheat Malt.

Roasting malt requires a great deal of expertise and experience on the part of the operator. It typically takes 3-4 hours to roast one 6,000-lb batch of malt, and almost an hour to cool. Many variables are involved that will lengthen or shorten the roasting process, so the operator must manually pull samples and compare them to a control to determine when the batch is finished and will match the target color specification.

This short video shows two drums rotating, and then an operator manually pulling a sample. The sample is cooled, ground and then compared to the control. When roasting is complete, the batch is dumped by opening the front “door”. Rotating arms that churned the malt during roasting continue to rotate, nudging the finished malt toward the front where it falls through a grate into a cooling bin.

Kilned and Roasted Malt

Kilned specialty malts have intense malty to biscuit flavors, and usually add light to rich golden color. Roasted caramel malts, which have had their starchy centers caramelized, are sweet with light caramel all the way to complex prune flavors and contribute amber to red to mahogany colors. So what happens when kilned malts are roasted?

This is where the maltster takes creative license, perhaps adding or decreasing moisture at certain stages and/or applying a variety of temperatures to develop interesting, complex flavors. Recipes are proprietary and difficult to reproduce. This is where the toasty, sourdough, coffee, cocoa, intense bitter flavors and brown to black colors are made. Usually used in small quantities, these unique specialties pack quite a punch in both flavor and color, and are an important tool in every craft and home brewer’s malt toolbox.